by Erin Pender and Megan Lorenz | July 29, 2022

Disability Pride Month, recognized and celebrated each July, seeks to “celebrate the intrinsic worth and meaningful contributions” of people with disabilities. Though not formally recognized yet by the United States, its roots go back over 30 years and stem from the historic Americans with Disabilities Act signed into law in 1990.

What is Disability Pride Month?

A group of disabled people and caregivers celebrating and supporting one another. Credit: Mashable

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a civil rights law; its purpose is to guarantee those with disabilities the same rights and opportunities as others. The ADA affords the same rights guaranteed regardless of race, color, religion, or sex, as in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, to disabled people.

Disability Pride Month began in Boston, where parades were held in 1990 and 1991 following the signing of the ADA. Though not formally recognized by the United States, the month of July was chosen for Disability Pride Month to honor the signing date of the ADA: July 26, 1990. Parades have since spread to other cities, including New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

The annual awareness month “seeks to celebrate the intrinsic worth and meaningful contributions” of people with disabilities. The main goals of Disability Pride Month and its celebrations are to foster appreciation for the disabled community and to truly listen to disabled people.

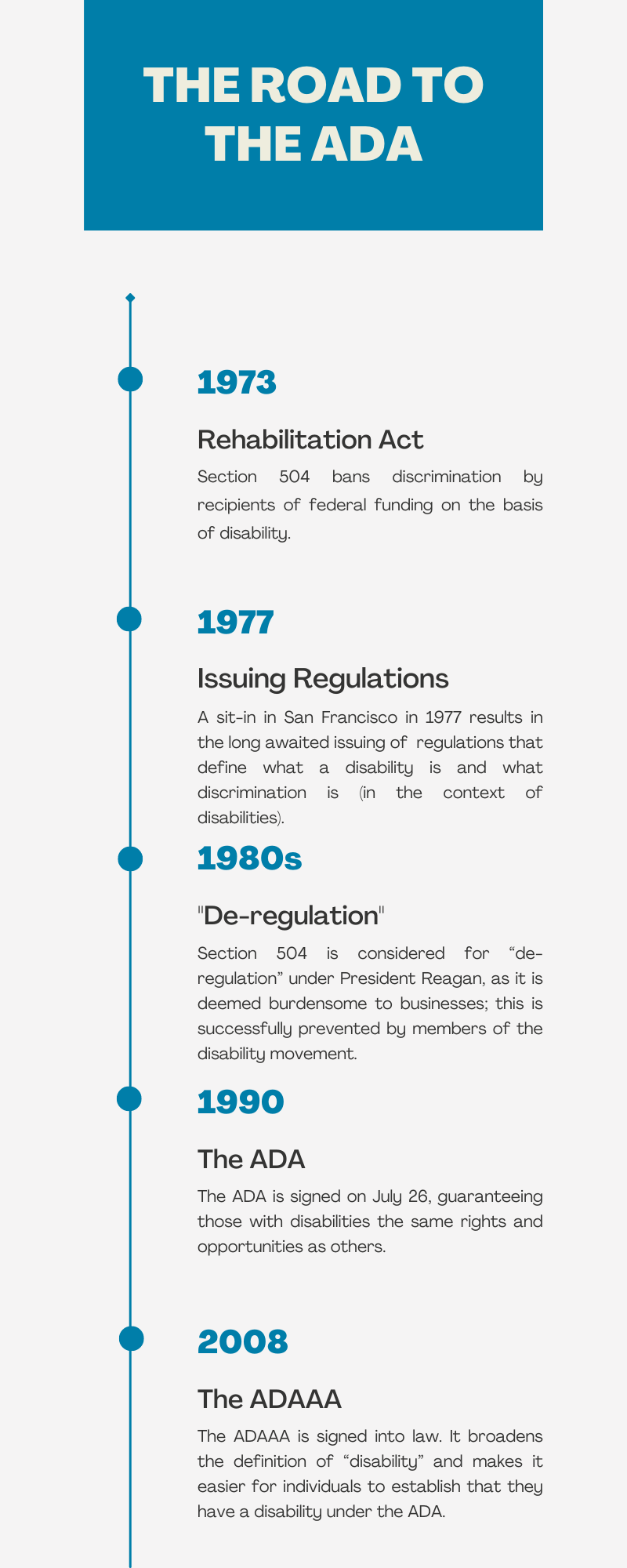

A visual depiction of The Road to the ADA, including the passing of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, regulations in response to a sit-in in San Francisco in 1977, the threat of de-regulation in the 1980s, the passing of the ADA in 1990, and the expansion of the ADA in 2008. Credit: Frenalytics

History of the Americans with Disabilities Act

Securing protections for Americans with disabilities was a long and hard fight. The first time that the mistreatment of people with disabilities was officially recognized as discrimination came in 1973, in the Rehabilitation Act.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 “prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities by any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance or by any program or activity conducted by a federal executive agency or the U.S. Postal Service;” in other words, it bans discrimination by recipients of federal funding on the basis of disability. Section 504 also required that regulations that defined what a disability is and what discrimination is (in the context of disabilities) be issued in order for the law to go into effect.

A sit-in in San Francisco in 1977 resulted in the long awaited issuing of these regulations. However, under President Reagan’s administration, Section 504 was one of the regulations considered for “de-regulation” as it was deemed burdensome to businesses. Members of the disability movement met with the Administration to educate then-Vice President George Bush on why this would be a bad move, and successfully prevented the de-regulation of Section 504. During these years, the mid-1980s, it became apparent that greater steps were needed to prevent discrimination; namely, more comprehensive civil rights legislation for people with disabilities.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was first introduced in 1988 and was signed on July 26, 1990. There are five titles to the ADA: Title I (Employment), Title II (State and Local Government), Title III (Public Accommodations), Title IV (Telecommunications), and Title V (Miscellaneous Provisions).

In 2008, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) was signed into U.S. law. The ADAAA broadens the definition of “disability” and makes it easier for individuals to establish that they have a disability under the ADA. According to the act itself:

To be protected by the ADA, one must have a disability or have a relationship or association with an individual with a disability. An individual with a disability is defined by the ADA as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.”

Though the ADA has certainly improved the protections in place for people with disabilities, it is not a final solution to the discrimination and difficulties faced by those people; rather, it is a building block for a more just future.

How the ADA Changed America

The ADA’s legislative impact was historic; it included discrimination bans across employment, public services, transportation, telecommunication, and public accommodation. Justin Dart, a chair of the National Council on Disability, said, “It is the world’s first declaration of equality for people with disabilities… It will proclaim to America and to the world that people with disabilities are fully human”.

The ADA began the process of making the world a more accessible place for the disabled by ensuring that public places were equipped with ramps, elevators, curb cuts, and more. It made travel easier by increasing the availability of wheelchair lifts, shuttle services, and rental cars with hand controls. Additionally, there was a rise in demand for interpreters for public communications. Finally, the ADA became a model for lawmakers around the world who seek to work to end discrimination.

Not only did the ADA provide non-discrimination laws and comprehensive protection for people with disabilities, but it also changed America’s attitude towards disability rights. Before the ADA, having a disability was widely seen as a medical problem to solve rather than an identity that is a part of human diversity. With the ADA in place, Americans began to understand that accommodations for the disabled is a civil right rather than a welfare benefit.

The Disability Pride Flag

The original version of the Disability Pride flag. Credit: Ann Magill

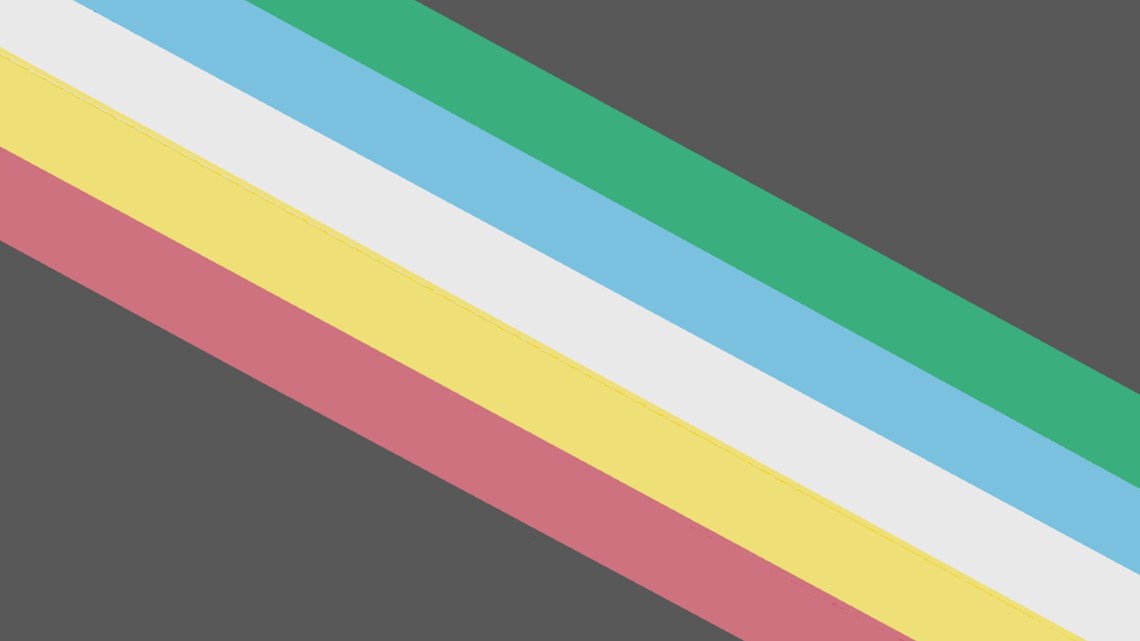

The updated version of the Disability Pride flag. Credit: Ann Magill

The Disability Pride Flag is revolutionary as it represents the struggle for rights of the disabled in the United States, underscored by the history of the ADA, while also expressing pride and further raising awareness of the injustice that is faced. The flag was created by Ann Magill, a disabled woman, and was influenced by movements such as LGBTQ pride and Black pride. The flag was created in 2019 but further changed in 2021 to have softer colors and straight diagonal stripes after receiving input from people with visually triggering disabilities.

Each of the features on the flag represent a different and distinct part of the disabled community:

- The Black Field represents disabled people who have lost their lives due to their illness, negligence, suicide, or eugenics.

- Red symbolizes physical disabilities.

- Yellow represents cognitive and intellectual disabilities.

- White indicates invisible and undiagnosed disabilities.

- Blue signifies mental illness.

- Green stands for sensory perception disabilities.

The variety of colors highlights how the term “disability” encompasses many different diagnoses, and gives equal value to each.

Here at Frenalytics, we aim to be a contributing factor in promoting welfare of the disabled and positively impacting lives today. Frenalytics focuses primarily on cognitive and intellectual disabilities with its personalized learning software for students and adults of all abilities, but we recognize and understand the wide scope of disabilities that deserve equitable attention.

The best ways to get involved are to learn, to educate others, and to support members of the disabled community. If you are interested in furthering your education and support of Disability Pride Month, we recommend reading Eight Ways to Celebrate Disability Pride Month.

Want to see how FrenalyticsEDU helps students with special needs live more independent lives?

Click here to learn more, or give us a call at (516) 399-7170.

Try FrenalyticsEDU for free!

Erin Pender is a junior at Boston College studying English, Marketing, and Biology. Her time at Frenalytics has allowed her to explore the business of helping others, and to gain new insights into special education and memory rehabilitation. Outside of work and school, Erin enjoys singing, being in nature, and volunteering with young students.

Contact Erin: erin@frenalytics.com

Megan Lorenz is a sophomore at Boston College intending to study Finance and Entrepreneurship. At Frenalytics, Megan is fascinated by the start-up culture as she is exploring different career paths and enjoys the human-centered approach of a sales position. In her free time Megan loves to play board games, connect with friends, and go on hikes.

Contact Megan: megan@frenalytics.com