by Erin Pender | August 3, 2022

Teachers play a major role in the development and growth of the next generation. Though their work is so important, teachers have long been overworked and underpaid. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the already present stressors and difficulties of a teacher’s day, leading to an increase in feelings of burnout among school staff.

A teacher with her head on her desk and hands down below her chair, showing physical signs of burnout. Credit: 1HOUR

What, exactly, is “burnout?”

Defined in 2003 by Christina Maslach as a “prolonged response to stressors in the workplace,” the World Health Organization describes burnout as including 1) exhaustion; 2) cynicism; and 3) inefficacy. Exhaustion from an overload of work leads to an actual stress reaction, resulting in mental distancing from the job and work relationships and a feeling of a lack of accomplishment. This can lead to a lower sense of self-efficacy, which correlates with a poorer teaching performance. Some signs of teacher burnout include fatigue, self-doubt, withdrawal, and loss of inspiration, as well as indications that teachers are considering leaving their jobs or feel that the career is not worth its high levels of stress.

How prevalent is burnout?

A number of surveys demonstrate the effects that the past few years, including the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, have had on teachers.

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that, since 2016, 270,000 teachers have left the profession, more than half of which were “occupational transfers,” or switches to another career.

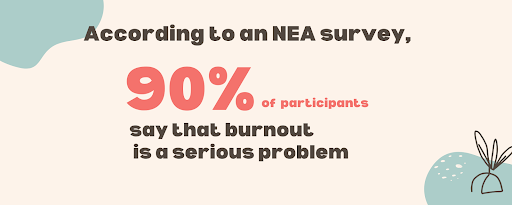

A statistic from an NEA survey showing how 90% of participants say teacher burnout is a serious problem.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of teachers reporting symptoms of burnout or thoughts of leaving their jobs increased:

- A National Education Association (NEA) survey in February 2022 found that 55% of education staff members are planning on leaving their profession earlier because of the pandemic, up from 37% in August 2021.

- 90% of participants in the February 2022 NEA survey said that burnout is a serious problem.

- 74% of those surveyed by NEA said they have had to fill in or take on other duties because of staff shortages.

- The National Center for Education Statistics reported that 20% of teachers have a second job to bolster their salaries – a pre-COVID trend that has increased since the start of the pandemic.

- Another survey from 2021 discovered that “[n]early four in 10 [educators] reported that working during the pandemic has made them consider changing jobs”.

- This same 2021 survey found that the factors which contributed most to this burnout were “COVID-19–related anxiety, anxiety about teaching demands, parent communication, and administrative support”.

These trends are not restricted to the United States. In a study of teachers in Germany, feelings of inefficacy increased as a result of burnout. In England in the fall of 2020, 81% of surveyed schools were concerned about the “impact of the pandemic on school staff, commenting on the increased workload, pressures on staff energy levels and social isolation;” in the spring of 2021, 69% were concerned “about staff safety and wellbeing, noting that staff were exhausted and at risk of burnout”.

What factors result in burnout?

Zoom became the primary teaching method during the pandemic, adding technology support to the ever-growing list of teachers’ responsibilities. Credit: Zoom

Many factors have led to the increase in feelings of burnout that has come with the pandemic. In particular, the increased job responsibilities and lack of support for teachers made their job much more demanding and much harder to balance. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the extreme stress that teachers were already under: making lesson plans, preparing between classes, and acting as not only a teacher but a friend and counselor for many students.

During and after the pandemic, a host of new difficulties and issues arose for teachers to tackle. Some of these were a lack of sufficient funding, high emotional demands and a lack of related training, inadequate preparation, and being placed in challenging situations, especially as the first line of communication with parents. With massive staff shortages, many teachers are being asked to perform additional tasks and therefore lose precious planning and break time, leading to an unsustainable increased burden on teachers; evidence also shows burnout may be disproportionately affecting teachers of color, as they face high levels of race-based stress.

Post-pandemic, teachers still feel undervalued and overburdened with catching students up on the material they missed as a result of the different and difficult learning styles of the pandemic, covering for other teachers, and trying to focus on the needs of their students. Contributing to this feeling of being unappreciated was some of the media coverage of teachers, which depicted learning gaps as the fault of the educators. As a team of academics studying the issue in England stated, “The general picture that is emerging is one of continuing dissatisfaction with pay and conditions, coupled with an ever-increasing workload and concerns about mental health and wellbeing”.

What do teachers think of burnout?

Many teachers express frustration with the increased expectations and responsibilities that have come in past years with little compensation or recognition.

A visual of one teacher dragging the weight of “school” behind their back to depict the stress and sustainability issues that come with the profession, based on EducationWeek’s findings. Credit: EducationWeek

Jennifer Sobieski, a high school special education teacher and Special Education Consultant at Frenalytics, discussed the difficulties that came with the pandemic, explaining that COVID-19 really changed teaching into an unstable career for many. The job description for teachers changed without warning; suddenly, educators were responsible for technology support, covering for other staff, observing safety procedures in the classroom, and working with students online and in person at the same time—all while trying to actually teach. Additionally, for Jen and other teachers, no salary increase has come with these additional responsibilities.

Denise Quinn, a permanent substitute teacher at Santapogue Elementary School on Long Island, NY said, of teaching currently, “It’s too intense.” She also touched on the disconnect between educators and administration, saying, “Most teachers look at teaching as an art, and most administrators look at teaching as a science.” The increased workload and regulations contribute to the feelings of burnout so many teachers are experiencing.

Another teacher at an elementary school on Long Island, NY stated, concerning the administrative changes, “It’s taken away my passion, a lot.”

What can be done to reduce burnout?

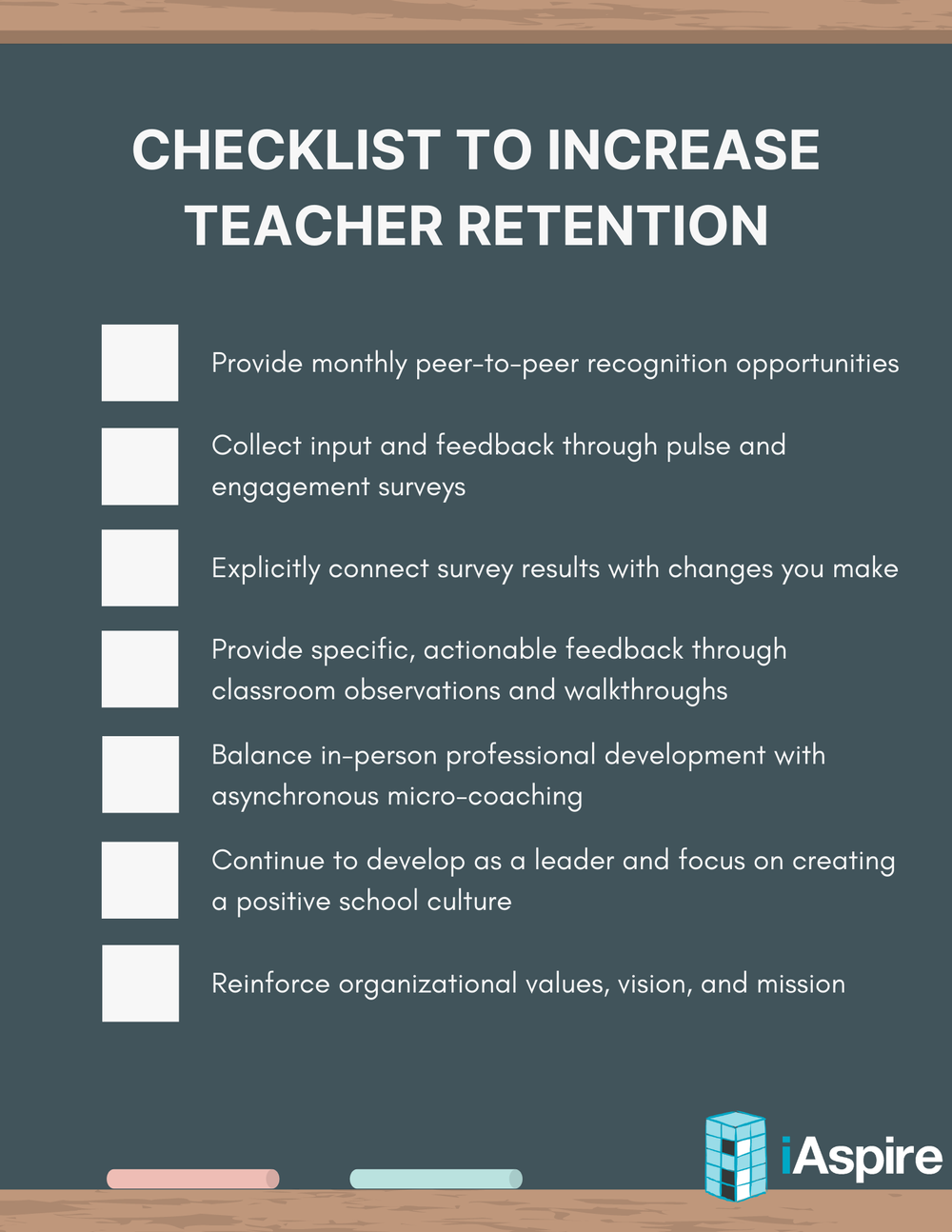

A checklist with suggested action items for school leaders to increase teacher retention, from iAspire. Items include collecting input and feedback from teachers through surveys, balancing in-person professional development with on-demand micro-coaching, and focusing on creating a positive school culture. Credit: iAspire

The issue of teacher burnout can be ameliorated through action by schools and efforts to create a more supportive professional culture. An NEA survey of its members sought to discover what strategies teachers thought could best address educator burnout; “raising educator salaries receives the strongest support (96% support, 81% strongly support), followed by providing additional mental health support for students (94% support), hiring more teachers (93%), hiring more support staff (92%), and less paperwork (90%)”. Various surveys and articles echo this same refrain: support is essential!

In all facets of the job, support and communication are key to lessening the burden on teachers, including in interactions with parents and when learning and using new technologies. Improving the everyday working conditions of educators is the best way to address burnout; some possible strategies to do so include better communication, targeted professional development, collaboration, fair expectations, and recognition. Increasing teachers’ involvement in goal-setting and decision-making, as well as conversing with them about how to achieve their teaching goals, can also help to prevent burnout. Additionally, mental health support is important.

To help build educators’ coping skills, schools can offer workshops, training, and counseling resources. Fostering inclusivity and providing mental health resources to teachers can also help those who are beginning to feel symptoms of burnout to cope. Sobieski echoed this, saying, “If there’s a psychologist for students, why don’t teachers have one too?” This kind of support, together with more recognition and involvement in decisions for teachers, can help to mitigate the effects of and hopefully prevent mass burnout in the future.

Next to parents, teachers play the second largest role in the growth and development of the next generation. During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the already intense demands on teachers have only grown. The dramatic increase in feelings of burnout among teachers points to a dire situation— one that calls for swift action to improve the working conditions of such important and necessary members of society.

Want to see how FrenalyticsEDU helps students with special needs live more independent lives?

Click here to learn more, or give us a call at (516) 399-7170.

Erin Pender is a junior at Boston College studying English, Marketing, and Biology. Her time at Frenalytics has allowed her to explore the business of helping others, and to gain new insights into special education and memory rehabilitation. Outside of work and school, Erin enjoys singing, being in nature, and volunteering with young students.

Contact Erin: erin@frenalytics.com